‘A small country with a big heart’ - Inside Cape Verde’s improbable journey from scrappy island nation to World Cup qualifier

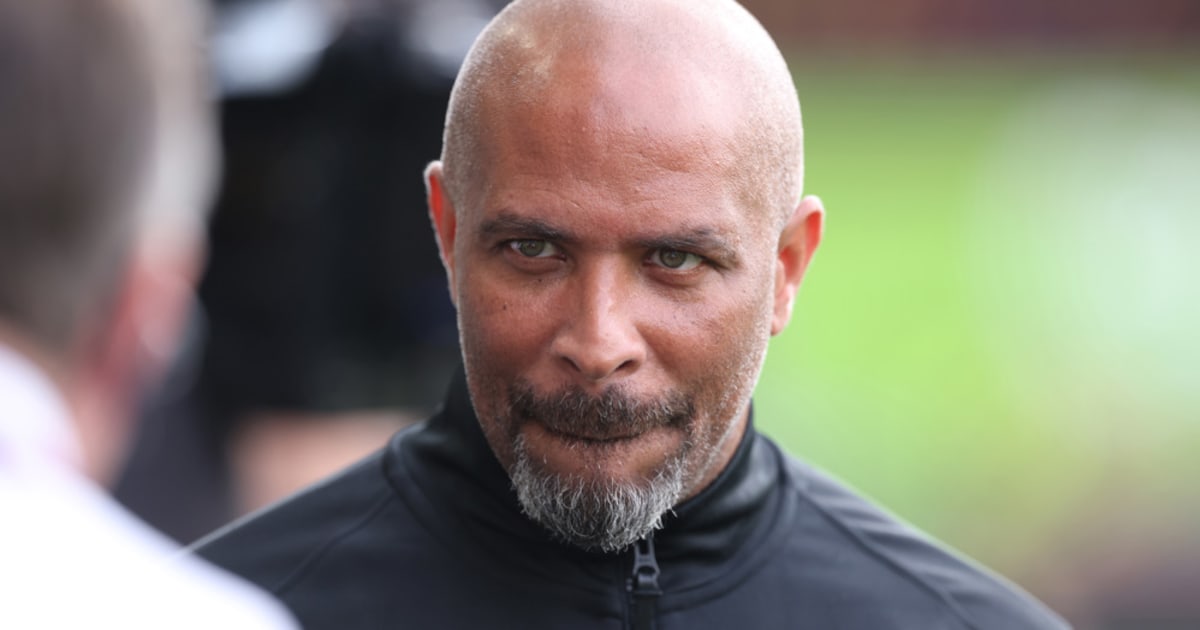

It must be emphasized, first, that this was very much a victory for the people of Cape Verde. They are the second smallest nation by population to qualify for a World Cup (pipped narrowly by Iceland to the top spot). They achieved independence from Portugal in 1975. They have had a football federation since 1982.They didn't join FIFA until 1986. And they have been involved in World Cup qualification fixtures for just more than 20 years.Recency has certainly has its impact. But this has also been a quick rise to global prominence. They qualified for the African Cup of Nations in 2013. That year, they made the quarterfinals. In 2023, they also advanced to the last eight - and lost to South Africa on penalties. And under current qualifying criteria, they would have had a shot to play on the world's stage four years ago.“With the first World Cup campaign, it was the old format where only five teams could qualify," defender Roberto Lopes said. "I mean, I already missed out on the play-off spot to Nigeria. But I think, off the back of our two Africa Cup of Nations (performances), we gained some confidence, saying that we can mix with the best teams. So, we didn’t fear who was in our group."There was an overwhelming sense that this has been coming. But that takes nothing away from what has happened this year. Head coach Pedro Leitao Brito, "Bubista", was born in Cape Verde and played for the national team for 16 years. He understands what this all means."It’s a victory that will lift our self-esteem,” Bubista said after his side secured qualification. “We know we’re still dealing with a lot of difficulties here. We’re a small country, but it’s only small on the map… a small country with a big heart."That they are. But for as much as Bubista and Co. have made all of the right moves - scouting, tactics, performing on the pitch - they have needed help. That is where FIFA comes in. There are countless countries every year that apply for membership, or that make the right moves to do so. But the barriers, mostly infrastructure and financial support, often lead to denials.FIFA has tried to change that, federation by federation, and country by country. That takes money. The governing body has come up with ways to help, starting with the FIFA Forward program, a designated fund that works to ensure that football development is possible in the nations that might not have the pieces in place to grow.It could mean anything from pitches to play on to kits to wear. Africa, in particular, has been a beneficiary. FIFA President Gianni Infantino announced last month that more than $1 billion has gone towards the African Football Federation and its 54 member associations in the last decade.As part of the project, FIFA estimated they would open 20-30 football academies by 2027. As of 2025, they have established 40, and 10 African teams could qualify for the World Cup. Representatives from 19 African nations competed at the Club World Cup last summer."Huge success this summer with four African teams," Infantino said last month. "But almost, I would say, more important, with African countries represented in the 32 clubs from all over the world."And Cape Verde is no different. Bubista said that when he first represented the national team, the country quite literally did not have kits to play in. This was a scrappy unit, with little money, scraping together what it could to organize friendlies and exhibitions. Growth, to be sure, has been organic. But FIFA has given them a lift.They have established artificial pitches on Santiago Island - one of a dozen islands that form the archipelagic state in the Atlantic Ocean, off the coast of West Africa - that have been used extensively for youth soccer. Their funding supported the renovation of the Aderito Sena Stadium, adding dressing rooms and seating that allowed the nation to host a 2022 World Cup qualifying fixture on home soil.More broadly, they have benefitted from participating in a pilot version of the FIFA Series, which allows teams from different federations to play friendlies against each other. There has been a backbone of support, with qualification coming due to their talent, their nous, and their belief."This victory also belongs to everyone who did their part and helped us," Bubista said after the final whistle. "In terms of organization, the federation has been doing a good job for everyone. When everything is in harmony, the players are united… all that helped us to get to this moment."Cape Verde might not be the only country to benefit. Getting into football federations is increasingly difficult. Staying there, though, is getting easier. And with every World Cup, the task gets a little lighter. FIFA Forward money comes from the global body's revenues, mostly the World Cup. It is distributed equally to member associations.The more money FIFA makes, in theory, the more it is able to distribute. A 48-team World Cup will have its critics, but there could be more Cape Verdes in the future. Member associations that have smaller revenues get more support for the basics: travel, accommodation, equipment.First time qualifiers Jordan and Uzbekistan have seen their soccer structures improved with financial injections. And last month, on a tiny island, a human triumph got a helping hand. And Cape Verde just might be the blueprint for sustained success.“I always said - I’ve already had the chance to say this at a CAF Conference - that if there were more spots, the smaller countries would have a bigger chance to fight," Bubista said. "It’s not only us. There are other countries fighting for a place in other parts of the world."

.jpg)